Published in PEPTalk Summer 2022 edition

Published in PEPTalk Summer 2022 edition

by Natalie O’Beirne

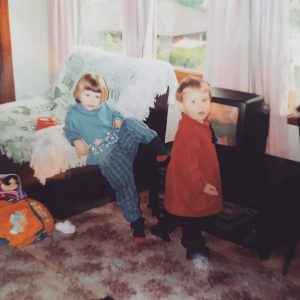

I grew up in what my family calls an ‘autism household.’

My twin brother Jacob (23) has autism, my younger brother Christian (16) has autism, and my older sister Claire (29) appears to have undiagnosed autism.

Then there was me. My childhood was very different to that of others. It was routine and at times rigid, strict and predictably unpredictable, the definition of organized chaos.

I, along with many other siblings in ‘autism households,’ matured very early into an adult, dealing with all the problems that came along with being a kid and teenager. I grew into the role of young carer in high school, helping my Mum get my siblings ready for school, breakfasted, clothed, and making sure teeth were brushed. I felt as though in a way I had begun co-parenting. I enjoyed talking to adults in my teenage years, I connected with them far more easily than peers. I struggled at times to achieve academically. In every school report I ever received, I was described as a quiet person who needs to learn to ask for help more often. It was difficult to make friends, I remember having big concerns about inviting friends over due to the unusual nature of our household.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (or A.S.D.) is described as a spectrum, but I believe it is more like a colour wheel with varied shades within colours. On this colour wheel my twin was blue and my younger brother red, I think these colours only go well together in toothpaste! A day growing up usually involved at least one meltdown by someone in the house, which usually triggered someone else’s meltdown, and so meltdown tennis ensued. Screaming, crying, broken items and gross bathroom stuff were the norms. My brothers both went through the initial Autism Spectrum Disorder diagnosis, then had their diagnoses reviewed when the list of Autism Spectrum Disorder labels was reduced. I remember the anxiety that was felt in my family with the news that my younger brother’s diagnosis was no longer going to be valid. Fortunately, both were able to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. I did feel left out a lot and wished I also had Autism Spectrum Disorder because it would get me the attention I felt I needed as a kid.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (or A.S.D.) is described as a spectrum, but I believe it is more like a colour wheel with varied shades within colours. On this colour wheel my twin was blue and my younger brother red, I think these colours only go well together in toothpaste! A day growing up usually involved at least one meltdown by someone in the house, which usually triggered someone else’s meltdown, and so meltdown tennis ensued. Screaming, crying, broken items and gross bathroom stuff were the norms. My brothers both went through the initial Autism Spectrum Disorder diagnosis, then had their diagnoses reviewed when the list of Autism Spectrum Disorder labels was reduced. I remember the anxiety that was felt in my family with the news that my younger brother’s diagnosis was no longer going to be valid. Fortunately, both were able to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. I did feel left out a lot and wished I also had Autism Spectrum Disorder because it would get me the attention I felt I needed as a kid.

Growing up with a twin with Autism Spectrum Disorder was very challenging. We were initially very close, but as I moved on to more complex play and stages in life, he didn’t move with me. In high school, kids worked out bullying my brother for having Autism Spectrum Disorder wasn’t going to get a reaction, he didn’t understand and was a very happy and bubbly person. So the attention was directed at me, and for most of my high school life, I wasn’t able to attend. I fell more and more behind and was diagnosed with many mental health conditions before the age of 15, all of these have been life-long.

One thing I did enjoy in high school was my psychology class. One of my proudest moments, one that would foreshadow my future, was the dreaded class presentation. We were tasked by the teacher to research a mental or neurological condition of our choice, create an informative presentation and present it to the whole class. I took the opportunity to educate some of my bullies, who were also in the class. I picked Autism Spectrum Disorder and I was enthralled. I compiled studies, facts, video simulations, easy read information, videos of people (specifically kids who were showing off what they’d achieved with their special interests) and put it all into a three-hour-long lecture. This took my teacher and everyone by surprise as I was known for never talking. At this moment I had found my passion without even realizing it, as well as my first A+.

I was noticing in high school that I was different from the others. I remember telling my Mum that I thought maybe I had Autism Spectrum Disorder, but she firmly told me this was not the case, I didn’t act like my brothers. We didn’t know that females with Autism Spectrum Disorder present differently. The kids my age seemed to be speaking a different language to me, my eating had become heavily restricted, I was feeling overloaded and overwhelmed every day. I had become so anxious that going to the letterbox would cause me to breakdown into tears. One day I went to the supermarket with my Mum. When I got to the grocery store entrance, I appeared to freeze, but my head whirled with overload from all the bright lights, loud and sudden sounds. Normal talking felt like everyone was yelling. I couldn’t get myself to walk forward into the shop and cried. I also saw social interaction with peers as a chess game. If I make this move or show this face, then they will most likely respond in this manner. I tested the boundaries of this and honed my skills in masking. Not to mention the fact that I still to this day love a good two-hour-long bath to regulate.

In college, my twin and I went to different schools. I didn’t need to be a parent at school anymore, so I flourished, excelled in my studies, made friends and went out often. I studied Early Childhood Education, as I was always commended for having a natural ability around kids. At 16, I had a job lined up in childcare for when I turned 18. In between, I stayed in school, got my Tasmanian Certificate of Education and became a trainer at my restaurant job. In college, I also opened my business selling products I created such as candles, soaps and other bath products. By year two, I had turned a profit and was selling in local shops.

At 18, I began working in childcare, earned my qualifications and kept with it for several years. Once again though, I had stumbled upon a niche within the work I was doing. I connected easily with the children in my childcare and after school care who had disabilities. I could speak fluently in ‘therapy talk’ when their allied health professionals came in and could pick up on the non-verbal signs that others couldn’t. It just clicked. I enjoyed meeting the families of the children and watching them through their diagnostic journeys. I felt like I could appreciate what they were going through. I also appreciated small victories in the day to day lives of the children when others only saw constant defeat. People would describe undesired actions of the children and I found myself saying more and more, ‘no that’s understandable, I’d be upset too’ or ‘fair enough.’ I even did a little therapy assistant work, having achieved my disability skillset (with a focus on Autism Spectrum Disorder) thanks to A.C.D. Tas’ very own Janet Presser.

At 18, I began working in childcare, earned my qualifications and kept with it for several years. Once again though, I had stumbled upon a niche within the work I was doing. I connected easily with the children in my childcare and after school care who had disabilities. I could speak fluently in ‘therapy talk’ when their allied health professionals came in and could pick up on the non-verbal signs that others couldn’t. It just clicked. I enjoyed meeting the families of the children and watching them through their diagnostic journeys. I felt like I could appreciate what they were going through. I also appreciated small victories in the day to day lives of the children when others only saw constant defeat. People would describe undesired actions of the children and I found myself saying more and more, ‘no that’s understandable, I’d be upset too’ or ‘fair enough.’ I even did a little therapy assistant work, having achieved my disability skillset (with a focus on Autism Spectrum Disorder) thanks to A.C.D. Tas’ very own Janet Presser.

I moved to Canada for a new experience and a fresh start when I turned 20. I travelled around Malaysia on the way through. I spent two years in Canada working as a tour guide, tour company receptionist, guest relations specialist (a fancy title I know, just wait though!), a guest service supervisor and a Survey Detractor Nominator Coordinator (I told you so, this was better known as a Complaints Manager).

Two years later we got the devastating news that Covid had now hit Australia, and all the toilet paper was now missing from Woolworths. The next announcement was that Australian citizens needed to come home before the borders closed, or risk being trapped without support. I had met an Australian/Canadian man in Canada, but as he was studying, I had to leave him behind at the airport terminal.

Four weeks of hotel quarantine later and I became a free citizen, roaming around my designated 10 kilometres of Hobart. With Vegemite toast in one hand and Milo in the other, I went job hunting. I had now worked in hospitality, childcare, retail and tourism. This made knowing what I wanted to do with the rest of my life very clear. I wanted to work in disability and help people like my family, people who I consider to be my community. In addition to my background in early childhood, this helped narrow the field.

I got a job as a Team Leader working in Supported Independent Living houses, that specifically supported teenagers. This was perfect. I built up a lot of experience during this time and learnt about a broader range of disabilities. I also studied and recently attained my Diploma of Leadership and Management. The study has become easier now, outside of the school environment. My diploma was scheduled to be a four-year course and I completed it in 6 months. After that, I became a Coordinator of Supports which allows me to once again work with my community. I also joined a group supporting the local Hazara community as a board member.

At 23 years old, I saved up my money and invested in some specialists’ opinions (also a nice car and clear braces). I found a reputable psychologist who specialized in Autism Spectrum Disorder, and heard the words ‘I agree with you, you are right, you have Autism Spectrum Disorder.’ After this news, I was a very sore winner. ‘I told you so’ was my favourite statement for a few weeks. People were concerned that I would be upset to receive a label, but I couldn’t have been prouder. Everything made sense, all my difficulties and the pathway forward. I’d spent my whole life advocating and supporting people who were just like me, and I felt honoured to have finally received my diagnosis and to be part of a group that is so diverse and truly fascinating to me. My brain is a different kind of brain to a lot of people’s, it’s also the same as theirs. I spent my life preparing and studying this neurological condition, helping others accept that they are different and not less, now I know that I have been fighting for myself and my future.

It has not been easy. I have had people tell me that they weren’t sure that I would make it through. I didn’t just make it through, I achieved. I missed out on a lot of education at school, I can’t use maths theory, add fractions or spell, I certainly don’t know my multiplications or division, I don’t know what a noun is and I was a selective mute in Primary School. But look what I accomplished regardless!

I love revealing to people not that I have Autism Spectrum Disorder, especially when they are focusing on the disabling parts of disabilities. I like to line up my achievements and then at the very end, destroy those misconceptions and stigma. I was worried at first about how my friends would react, but I think I have changed their minds on what Autism Spectrum Disorder looks like. I educated those around me whenever I could years before diagnosis. I wanted them to know that a disability is not a life sentence, it’s often just an obstacle. For some people, it’s a hurdle and for others, it could look like a mountain.

My Autism Spectrum Disorder means that I’m socially awkward, I mess up a lot and get burnt out and overwhelmed. It also means that I am logical, I am a great analyst, and I can see patterns that aren’t obvious to others. I can communicate well with other neurodivergent people and help them, I pick certain things up easily and my routine thinking means that I am a master at sticking to schedules. I also know a lot of random facts about very random things. This is especially fun when I find someone else with special interests and we have what I like to call ‘a special interest off’ (verbal vomit of completely unrelated fact dumping).

Autism Spectrum Disorder can be more severe, but for me when I’m working with those people who struggle more, I see their accomplishments in their grand entirety, even if it’s just making the bed for the first time. All achievements are achievements, they are worth being proud of. Those little achievements are at times what I aim for when I’m overwhelmed, they are the best because, at my lowest, they take a mammoth amount of effort and energy.

My old team in Canada often remind me, when mimicking my Australian accent, that I say ‘credit where credit’s due’ and ‘keep on keeping on’ a lot.

I stand by those sayings every day and they keep me moving forward. I never give up!